Kellia and Pherme

The remains of over one thousand five hundred early Christian monastic structures lie in the desert at the western margin of the Egyptian Delta. In antiquity, because of the many hermitages that dotted the landscape, the main settlement in the area came to be named Kellia (“The Cells”). Another settlement called Pherme developed as a satellite community to the larger one at Kellia.

Both sites are well known from ancient sources like the Sayings of the Desert Fathers (Apophthegmata Patrum), a collection of anecdotes relating to the earliest generations of Egyptian monks.[1] Monasticism at Kellia and Pherme combined elements of the solitary and communal life. While there was ample opportunity for monks to find solitude in individual dwellings (i.e. cells), many lived together in pairs or groups of three and gathered with other monks weekly for worship. This way of life continued until the eighth century, when these settlements declined under early Arab rule.

The many mud brick dwellings that made up each settlement were scattered throughout the desert landscape, grouped in clusters on low natural mounds. They date primarily to the fifth, sixth and seventh centuries. Many of the dwellings were very long-lived, with multiple changes and additions during their lifespan. Although there was a great range in size and complexity, most dwellings shared the same basic rectangular shape, usually divided into a courtyard and a complex of rooms. These included kitchens, latrines, offices, storage spaces and rooms for worship. Many of the rooms were coated with white plaster with painted wall writings (dipinti) and motifs dominated by crosses and vegetation. This visual style is characteristic of both Kellia and Pherme and contrasts with other monasteries of the time, such as those at Saqqara and Bawit, which typically included figures and geometric elements.[2]

Brief Archaeological History of Kellia and Pherme

The site of Kellia is positioned some 60 km south east of Alexandria at the western edge of the Delta, with the satellite settlement of Pherme eleven kilometers southeast of central Kellia. After abandonment, the exact location of these important late antique monastic settlements was lost until their rediscovery in 1964. French and Swiss teams began archaeological investigation the next year, continuing until 1990. They aimed to locate all the ancient remains in the 126 square kilometer (12, 600 hectare) Kellia-Pherme site through topographical survey and mapping, documenting the basic layout of each structure from the surface traces of its architecture visible in the morning dew. Selective full and partial excavation of individual dwellings provided insights into their construction and organization, and how they changed over time. These data allowed the development of typologies of architectural space and of building types that could be traced across the site. The dipinti, visual programs, pottery and objects also supplied dating evidence and a wealth of information about the lived experience of monasticism at Kellia.[3]

Throughout this period, the French and Swiss teams had to contend with significant threats to the site’s preservation. In the 1960s, the Egyptian government began intensive efforts to reclaim desert territories and develop agriculture through irrigation in the western Delta hinterland. The result was a rising water level that increasingly saturated and destabilized the ground in and around the monastic remains. Each year, portions of the site were lost to unmonitored agricultural expansion, and in 1990 archaeological work at Kellia was suspended. The cluster of monastic remains at Pherme fortuitously escaped this fate because of their slightly higher elevation. The ancient settlement is divided into two distinct areas, Pherme North (Quṣūr Hégeila/ Quṣūr Ḥijaylah) and Pherme South (Quṣūr ‘Éreima/ Quṣūr ‘Iraymah), each today consisting of over fifty mud brick buildings (fig. 1).Only about ten of these were excavated by the Swiss during their three seasons of work here from 1987 to 1989.[4]

Figure 1. Previously excavated monastic cells at Pherme (2005).

In 2006, at the invitation of members from the former Swiss team, the Yale Monastic Archaeology Project (YMAP-North), led by Stephen J. Davis (project director and principle investigator) and Darlene Brooks Hedstrom (archaeological director) resumed archaeological work at Pherme. Its aim was to continue the work of the Swiss and French teams through a series of geophysical surveys and small-scale excavations.[5]

Magnetometry Survey

The surveys used magnetometry, a geophysical technique that detects archaeological features below the ground through the contrast between their magnetic field and those of adjacent sand.[6] Although mud bricks usually show a strong contrast due to their high iron content, it was much lower than usual at Pherme because of the bricks’ high sand content. The geophysical survey, conducted by Tomasz Herbich (assisted by Artur Buszek and Jakub Ordutowski), covered a total area of 4 hectares and targeted areas that were densely populated with buildings only partially documented by the Swiss team. It aimed to confirm and expand upon the data collected through different and less precise methods in the earlier work.

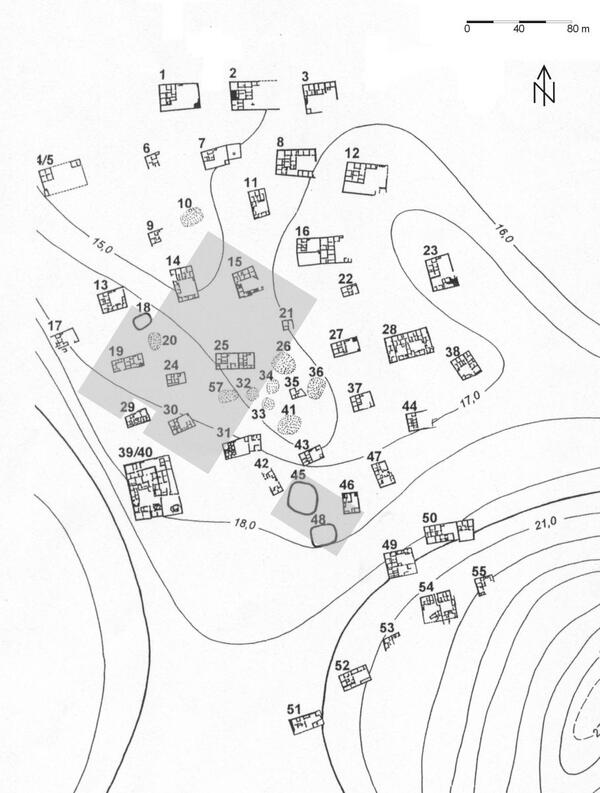

The magnetometry survey of Pherme North covered a total area of 1.96 hectares and included several buildings and other features investigated by the Swiss team. It was able to confirm the general distribution of dwelling. However, the position of a few of the hermitages did not match the published map, with one (QH 14) in reality some 20 m south of its mapped location (fig. 2). Anomalous features noted by the Swiss team but without any architectural remains that would confirm them as belonging to buildings were also investigated. These were often associated with pot sherds, which show up well in magnetometry images because of their high iron content. Instead of buildings, they were probably the locations of middens for trash disposal.

Figure 2. Pherme North. Magnetometry map showing correct location of QH 14.

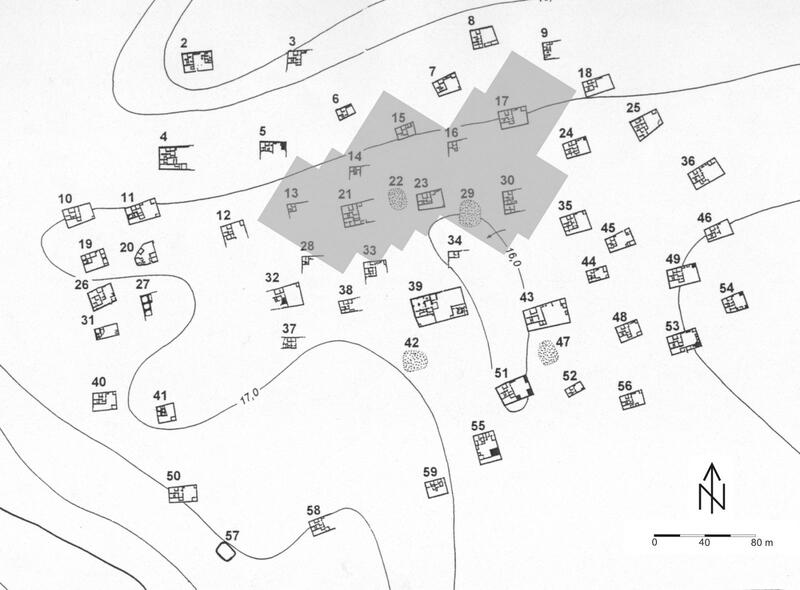

At Pherme South (Qusûr ‘Éreima), the magnetometry survey covered 2.16 hectares in the center of this area (fig. 3). Here too, it was possible to update the position and extent of some of the buildings. Oval anomalies with relatively high or high magnetic values consistent with ovens or furnaces were also detected inside some of the hermitages. Those located in spaces interpreted as kitchens are likely to be ovens, but others may instead be large ceramic vessels or sherds that were used architecturally and embedded in the walls.

Figure 3. Pherme South. Location of magnetic survey.

Excavation

Excavations by Darlene Brooks Hedstrom, with the assistance of Chrysi Kotsifou, Paul Dilley, and Christine Luckritz Marquis, focused on two mounds at Pherme South. Other archaeological activity at these locations included mapping by Dawn McCormack and the recording of ceramics and other materials by Gillian Pyke and Barbara Emmel. IT support was provided by Mark Brooks Hedstrom. The two mounds were selected for limited surface clearance in order to clarify their layout and investigate the nature of associated deposits and finds. The wall-tops were revealed at a depth of 5 cm below the surface, with evidence for wall collapse into the rooms. A deposit of fine grey ash inside one space suggests that this was a kitchen. The recovered pottery from both excavations was consistent with material found in these locations by the Swiss team.

Further Reading

Alès, Jean-Marie, et al., eds. Survey archéologique des Kellia (Basse-Égypte). Rapport de la campagne 1981. EK 8184, vol. 1. Mission suisse d’archéologie copte de l’Université de Genève. Louvain: Peeters, 1983.

Ballet, P., N. Bosson, and M. Rassart-Debergh, Kellia II. L’ermitage copte QR 195. II. Céramique, inscriptions, décors, Fouilles de l’IFAO 41. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 2000.

Bridel, P. ed. Le site monastique copte des Kellia. Sources historiques et explorations archéologiques. Actes du colloque de Genève 13 au 15 août 1984. Geneva: University of Geneva, 1986.

Bridel, P., N. Bosson and D. Sierro, eds. Explorations aux Qouçoûr el-Izeila lors des campagnes 1981, 1982, 1985, 1985, 1986, 1989 et 1990. EK 8184, vol. 3. Louvain: Peeters, 1999.

Bridel, P., and D. Sierro, eds. Explorations aux Qouçoûr Hégeila et ‘Éreima lors des campagnes 1987, 1988 et 1989. EK 8184, vol. 4. Louvain: Peeters, 2003.

Bridel, P., and N. Bosson, eds. Explorations aux Qouçoûr er-Roubâ’îyât. Rapport des campagnes 1982 et. EK 8184, vol. 2. Mission suisse d’archéologie copte de l’Université de Genève. Louvain: Peeters, 1994.

Coquin, R.-G. “Kellia: French Archaeological Activity.” In The Coptic Encyclopedia. Ed. A.S. Atiya. Volume 5, 1398–1400. New York: Macmillan, 1991. Available at: https://ccdl.claremont.edu/digital/collection/cce/id/1156/rec/1.

Daumas, F., and A. Guillaumont. Kellia I, Kom 219. Fouilles exécutées en 1964 et 1965. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1969.

Davis, S. J. “Completing the Race and Receiving the Crown: 2 Timothy 4:7–8 in Early Christian Monastic Epitaphs at Kellia and Pherme.” In Asceticism and Exegesis in Early Christianity, ed. H-U. Weidemann. Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, 334-73. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2013.

Descœudres, G. “L’architecture des ermitages et des sanctuaries.” In Les Kellia. Ermitages coptes en Basse Égypte. Ed. Y. Mottier and N. Bosson, 33–55. Genève: Musèe d’art et d’histoire de Genève, 1989.

Egloff, M. Kellia. La poterie copte. Quatre siècles d’artisanat et d’échanges en Basse-Égypte. Recherches suisses d’archéologie copte III, Geneva: Georg, 1977.

Guillaumont, Antoine, et al. “Kellia: History of the Site.” In The Coptic Encyclopedia. Ed. A.S. Atiya. Volume 5, 1397–98. New York: Macmillan, 1991. Available at: https://ccdl.claremont.edu/digital/collection/cce/id/1156/rec/1.

Guillaumont, A. “Une inscription sur la ‘prière de Jésus.” Orientalia Christiana Periodica 34 (1968), 310–25.

Guillaumont, A. “Histoire des moines aux Kellia.” Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 8 (1977), 187–203.

Guillaumont, A. “Le site des Kellia manacé de destruction.” In Prospection et sauvegarde des antiquités de l’Égypte, ed. N.-C. Grimal. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, 1981.

Henein, Nessim H., and M. Wuttmann. Kellia. II. L’ermitage copte QR 195. I. Archéologie et architecture. Plans. Fouilles de l’IFAO 41. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 2000.

Herbich, T., D. Brooks Hedstrom, and S. J. Davis, “A Geophysical Survey of Ancient Pherme: Magnetic Prospection at an Early Christian Monastic Site in the Egyptian Delta,” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 44 (2007), 129–37.

Jarry, J. “Description des restes d’un petit monastère coupe en deux par un canal d’irrigation aux Kellia.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 66 (1968), 147–55.

Kasser, R., ed. Kellia 1965. Topographie générale, mensurations et fouilles aux Qouçoûr ‘Îsâ et aux Qouçoûr el-‘A’Abîd, mensurations aux Qouçoûr el-‘Izeila. Recherches suisses d’archéologie copte, volume 1. Genève: Georg, 1967.

Kasser, R., ed. Kellia. Topographie. Recherches suisses d’archéologie copte, volume 2. Genève: Georg, 1972.

Kasser, R.. Le site monastique des Kellia (Basse-Égypte). Recherches des années 1981–1983. Mission suisse d’archéologie copte de l’Université de Genève. Louvain: Peeters, 1984.

Rassart-Debergh, M. “Kellia: Paintings,” In A.S. Atiya, ed., The Coptic Encyclopedia. Volume 5, 1408–9. New York: Macmillan, 1991. Available at: : https://ccdl.claremont.edu/digital/collection/cce/id/1156/rec/1.

Weidmann, D. “Kellia: Swiss Archaeological Activity.” In A. S. Atiya, ed., The Coptic Encyclopedia. Volume 5, 1400–6. New York: Macmillan, 1991. Available at: : https://ccdl.claremont.edu/digital/collection/cce/id/1156/rec/1.

Weidmann, D. Kellia. Kôm Qouçoûr ‘Îsâ. Fouilles de 1965 à 1978. Recherches suisses d’archéologie copte. Volume 4. Louvain: Peeters, 2013.

[1] See: B. Ward, The Sayings of the Desert Fathers: The Alphabetic Collection, rev. ed. (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1984); J. Wortley, The Book of the Elders: Sayings of the Desert Fathers, The Systematic Collection (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2012); John Wortley, The Anonymous Sayings of the Desert Fathers: A Select Edition and Complete English Translation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

[2] M. Rassart-Debergh, “Quelques croix kelliotes,” in Nubia et Oriens Christianus. Festschrift für C. Detlef G. Müller zum 60. Geburtstag, ed. P. O. Scholz and R. Stempel (Bibliotheca Nubica 1; Cologne: Dinter, 1987),373–385; M. Rassart-Debergh, “Richesses des peintures kelliotes,” in Études coptes VII. Neuvième journée d’études, Montpellier 3-4 juin 1999, ed. N. Bosson (Louvain: Peeters, 2000), 207–233; J. E. Quibell, Excavations at Saqqara (1906-1907) (Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1908); J. E. Quibell, Excavations at Saqqara (1908-9, 1909-10), The Monastery of Apa Jeremias (Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1912); J. Clédat, Le monastère et la necropole de Baouît, 2 volumes (Mémoires de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 12; Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1906); J. Maspero, Fouilles exécutées à Baouît (Mémoire de l’institut français d’archéologie orientale 59; Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1931).

[3] For an overview of the site, see https://ccdl.claremont.edu/digital/collection/cce/id/1156/rec/1. For the lived experience at Kellia, see P. Bridel, ed., Le site monastique copte des Kellia. Sources historiques et explorations archéologiques. Actes du colloque de Genève 13 au 15 août 1984 (Geneva: University of Geneva, 1986); S. J. Davis, “Completing the Race and Receiving the Crown: 2 Timothy 4:7-8 in Early Christian Monastic Epitaphs at Kellia and Pherme,” in Asceticism and Exegesis in Early Christianity, ed. H-U. Weidemann (Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2013), 334–373.

[4] P. Bridel and D. Sierro, eds., Explorations aux Qouçoûr Hégeila et ‘Éreima lors des campagnes 1987, 1988 et 1989 (EK 8184, volume 4; Louvain: Peeters, 2003).

[5] For a full account of this work, see T. Herbich, D. Brooks Hedstrom, and S. J. Davis, “A Geophysical Survey of Ancient Pherme: Magnetic Prospection at an Early Christian Monastic Site in the Egyptian Delta,” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 44 (2007), 129–137.

[6] For more on this technique, see J. W. E. Fassbinder, “Magnetometry for Archaeology,” in Encyclopedia of Georarchaeology, ed. A. S. Gilbert (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2017), 499–514.