Residence B

From 2006 to 2012, the YMAP-North team conducted excavations of a mudbrick monastic dwelling, labeled as Residence B.

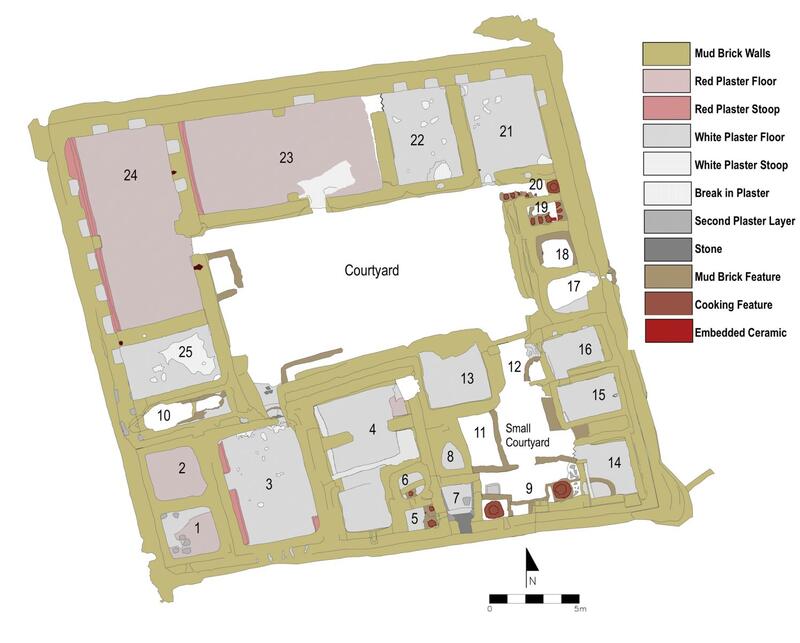

Figure 1. Plan of Residence B with color-coded key.

Residence B was selected for excavation because the size of the mound indicated that it is the smallest of the three buildings lying in close proximity to the midden (fig. 1). It was excavated in 2007–2010 under the archaeological direction of Darlene Brooks Hedstrom with mapping by Dawn McCormack in 2010 (assisted by Elizabeth Davidson and Sean Urruita), and under the archaeological direction of Gillian Pyke with mapping by Elizabeth Davidson in 2012. The excavators were: Kristen Baldwin Deathridge (2009), Dylan Burns (2008), Emily Cocke (2007–2009), Jacqueline Cooper (2009–2010), Elizabeth Davidson (2009–2010, 2012), Paul Dilley (2007–2009), Eden Fann (2009), Erin Gorman (2007); Nikki Kettleshake (2007), Mohammed Khalifa (2007–2010), Ashley Klingelhoefer (2010), Chrysi Kotsifou (2007–2010), Stephanie Livingstone (2008), Christine Luckritz Marquis (2007–2010), Erene Marcos (2008), Jacqueline Nair (2009–2010), Trinity Rufus (2007), Daniel Schriever (2010), Fouad Shaker (2007–2009), and Whitney Yount (2009–2010).

Field registration of excavated materials was in the care of Barbara Emmel (2007–2008), Christine Luckritz Marquis (2009) assisted by Agnieszka Szymanska, and Agnieszka Szymanska (2010 and 2012) assisted by Ashley Klingelhoefer (2010). Fallen plaster was recorded by Barbara Emmel (2007–2008), Gillian Pyke (2009–2010, 2012), Agnieszka Szymanska (2009–2010, 2012) and Christine Luckritz Marquis (2009). Building conservation was undertaken by Lamia al-Hadidi in 2008–2010. Computer systems support and database management was provided by Mark Brooks Hedstrom. Five study seasons were dedicated to analysis of recovered materials in 2011, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2017.

Figure 2. Room 24 of Residence B (Room 24) shown after excavation, with Liz Davidson and Mary Farag recording the building in the foreground and Dar Brooks Hedstrom brushing the surface of a wall in the background.

The building is a case-study for the construction, organization, and modification of the dwellings of the Monastery of John the Little (fig. 2). The residence’s visual program and wall writings speak to practices of prayer and remembrance. Items of material culture, such as pottery, glass, and objects, give a sense of the everyday life of the monastic household. Plant and animal remains provide important data about their dietary habits and local environmental conditions. The pottery assemblage places the final occupation of the residence to the late ninth century CE. This shows that this style of monastic organization, known at Kellia in the late antique period, survived at the Monastery of John the Little into the early medieval period. Two wall writings (dipinti), dated to 956/57 and 985/86 CE, respectively, suggest that the use of the building as a place of visitation continued into the late tenth century.

The architecture, building materials, and organization of Residence B, as well as its archaeological deposits, have been studied by Darlene Brooks Hedstrom. The multi-room monastic dwelling, measuring 25 x 25 m, is constructed in mud brick and organized around a central courtyard. It is very well preserved. The walls survive up to 2.5 meters in height in some places, to above the level of the door archways and vault springs. Its entrance is located on the east side, leading through a vestibule to the central courtyard from which the rooms, including several kitchens and a second courtyard, are accessed. Most of the rooms originally had domed or barrel-vaulted roofs (now lost), with lime-plastered ceilings, walls, and floors. Some are furnished with filtered windows or airshafts for airflow and glazed windows for natural light (fig. 3). None of the glazed windows survived in situ but several examples were reconstructed by Gillian Pyke and Agnieszka Szymanska, and drawn by Pieter Collet. The window panes were included in Marie-Dominique Nenna’s study of the glass.

Figure 3. North wall of Room 3 with narrow vertical airshafts (left and centre). Note also the added doorway (right).

Ceramic vessels embedded in ceilings provided light, while those in floors received props to hold doors open. Vessels embedded in walls had various other functions: in Kitchen 9 west, they perhaps operated as cupboards/niches (fig. 4). Sherds were also included in the modeled mud structures of ovens and other cooking installations within the kitchens. The architectural use of pottery within this building has been investigated by Gillian Pyke and Darlene Brooks Hedstrom.[1]

Figure 4. Ceramic wall emplacements and modeled mud oven in Kitchen 9 west.

Most of the architectural features and building techniques observed in Residence B were also used at Kellia, showing that there was a high degree of regional continuity in the construction, organization, and use of domestic space in monastic dwellings throughout the late antique and early medieval periods.[2] Like the Kellia dwellings, there is evidence that Residence B underwent many changes during its life. Spaces were reconfigured by adding new walls, or even rooms, and access routes were altered through the blocking or cutting of doorways.

The lime-plastered walls of many of the rooms were painted with crosses and wall writings, with more extensive programs in Rooms 3 and 4a. Much of the plaster from the upper portions of the walls, where painted elements were generally positioned, fell during post-abandonment episodes of collapse. The fallen motifs and texts were painstakingly reassembled by Gillian Pyke and Agnieszka Szymanska, with assistance from Christine Luckritz Marquis in 2009 (fig. 5). The painted inscriptions (dipinti) have been transcribed, translated and studied by Chrysi Kotsifou, with further thematic investigations by Stephen Davis.

Figure 5. Agnieszka Szymanska reassembling painted scenes from Room 3.

Room 3, probably originally an oratory for prayer, shows evidence of a dynamic visual and textual program spanning the residential and visitation phases of Residence B. It includes a series of figural scenes, including equestrian martyrs such as Claudius and Victor (fig. 6) and the monastic saints Onophrius and Paphnutius, as well as Christ represented as the Lamb of God.[3]

Figure 6. Reassembled fragmentary painting of an equestrian martyr, from Room 3 of Residence B.

Two painted prayers include dates. One, addressed to Jesus Christ, is dated to 956/957 CE. The other was written twenty-nine years later, in 985/986 CE. An undated prayer by a certain Papa Iō, probably a member of the local community, is directed to Saint Shenoute, whose cult was prominent in medieval Scetis fig. 7).[4]

Figure 7. A painted inscription (dipinto) containing a prayer or petition to Saint Shenoute.

Pottery, glass, and objects provide insights into the daily life of the inhabitants of the monastic dwelling. The ceramic assemblage was studied by Gillian Pyke, assisted by Agnieszka Szymanska and Mohammed Khalifa. It is typical of a late ninth century household and includes vessel types for food storage, preparation, and cooking, as well as for dining. Storage vessels include bag-shaped transport jars used for the long-distance trade of food commodities. The cooking vessels, like those in the midden, had cut-rims. Although some dining vessels were polished, others were glazed, a technology newly introduced during that period. Petrographic analysis by Mary Ownby in 2013–2014 showed that some of the transport vessels originated in the east Mediterranean seaboard and that Aswan was a source for transport jars and dining vessels (fig. 7).[5] According to Marie-Dominique Nenna’s study, glass vessels, especially stemmed goblets and bowls, were also used for dining. The relatively few objects found were often very fragmentary. They were studied and documented by Gillian Pyke, assisted by Mary Farag and Agnieszka Szymanska, and drawn by Pieter Collet during the spring 2014 study season. Investigative and remedial conservation of the metal objects was carried out by Hazel Gardiner in 2017.

Figure 8. Mary Ownby preparing thin sections of pottery for petrographic analysis.

Plant materials from archaeological deposits within Residence B were studied by Mennat-Allah El Dorry, forming the subject of her doctoral research at the University of Münster.[6] These were mainly recovered from cooking installations, where some had been used as fuel and others, probably cooking waste, had been disposed of by burning. The fuel took the form of dung discs, a mixture of cow- or donkey-dung mixed with chaff or straw temper that was made into patties and dried. The plant species used for fodder were mainly weeds, with some barley, and the temper was from durum wheat and barley. The cooking waste included wheat, various pulses, grapes and dates. Some of the pulses showed evidence of processing techniques that still form part of Egyptian cuisine today. Animal bones and shells were analyzed by Salima Ikram, who found that these were dominated by fish. As was the case in the midden, the most common mammals were pig and sheep/goat, usually lambs or sheep.

Figure 9. Whitney Young excavating the skeleton of a dog.

[1] G. Pyke and D. Brooks Hedstrom, “The Afterlife of Sherds: Architectural Re-use Strategies at the Monastery of John the Little, Wadi Natrun,” In Functional Aspects of Egyptian Ceramics in Their Archaeological Context, ed. B. Bader and M. F. Ownby (Leuven 2013), 307–326.

[2] For the architecture and construction of a comparable dwelling at Kellia, see: Henein and Wuttmann, Kellia 2.

[3] For a consideration of the scene of Onophrius and Paphnutius in the context of monastic commemoration, see Stephen J. Davis, “Curriculum Vitae et Memoriae: The Life of Saint Onophrius and Local Practices of Monastic Commemoration,” in From Gnostics to Monastics: Studies in Coptic and Early Christianity, ed. D. Brakke, S. J. Davis, and S. Emmel (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 263; Leuven: Peeters, 2017), 383–391.

[4] For these three texts, see: Stephen J. Davis, “Shenoute in Scetis: New Archaeological Evidence for the Cult of a Monastic Saint in Early Medieval Wādī al-Naṭrūn,” Coptica 14 (2015), 1–19.

[5] These include the Nebi Samwil-type jar, the characterization of which is based in part on examples from the Monastery of John the Little: see A. L. Gascoigne and G. Pyke, “Nebi Samwil-type Jars in Medieval Egypt: Characterisation of an Imported Ceramic Vessel,” in Under the Potter’s Tree: Studies on Ancient Egypt presented to Janine Bourriau on the occasion of her 70th birthday, ed. David A. Aston, Bettina Bader, Carla Gallorini, Paul Nicholson, and Sarah Buckingham (Leuven: Peeters, 2011), , 417–431.

[6] M.-A. El Dorry, Monks and Plants: A Study of Foodways and Agricultural Practices in Egyptian Monastic Settlements, PhD. Dissertation submitted to the Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität, Münster, 2015. See also: M.-A. El Dorry, “Monks and Plants: Understanding Foodways and Agricultural Practices in an Egyptian Monastic Settlement,” in L. Doppler, P. Fischer-Schröter and M. Schröder, eds. Work in Progress. Work on Progress. Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft. Doktorand_innen-Jahrbuch 2015 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, Hamburg 2015, 218-227.