Church

The main church at John the Little was partially excavated in the 1990s by a team sponsored by the Scriptorium of Calvin Theological Seminary.

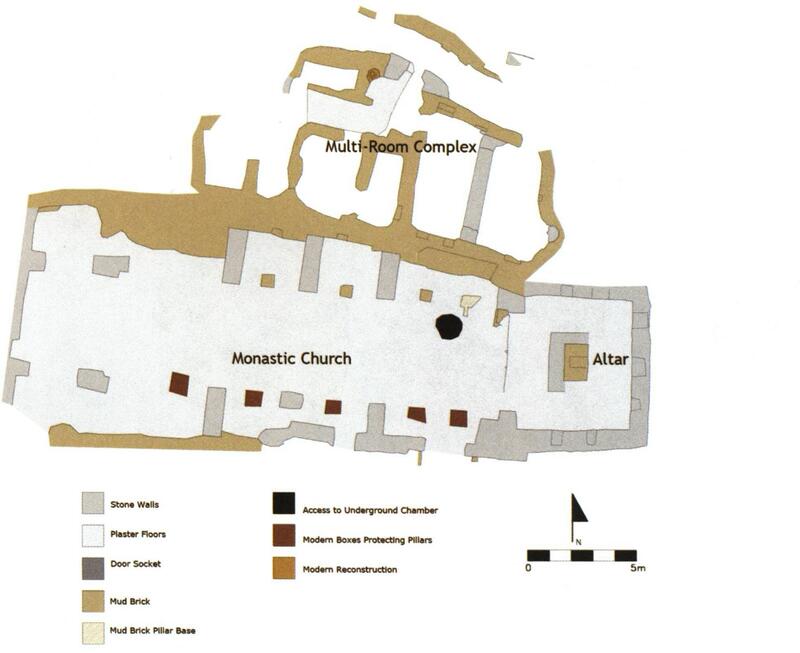

After its excavation, the structure suffered considerably from exposure to the elements and from vandalism (fig. 1). In order to document its present state, YMAP-North incorporated the church and its immediate environs into its geophysical and archaeological surveys. The area to the south of the church was included in the geophysical survey conducted by Tomasz Herbich, assisted by Artur Buszek and Jakub Ordutowski in 2006. Dawn McCormack completed an archaeological survey of the church in 2006–2007 (fig. 12).

Figure 1. The main church at John the Little in 2006, viewed from the west.

Bishop Samuil and Peter Grossmann describe the church as a three-aisled basilica-type church with peculiarly narrow returning aisles and an entrance on the south side of the nave.[1] The original walls are probably those built of mud brick. Those in stone, including the large square sanctuary and the long piers connecting some of the columns to the walls of the nave, represent later alterations. The configuration of the church is unusual, making it difficult to date, but the addition of a sanctuary without side chambers is also a feature of the church at the nearby so-called Monastery of Moses the Black.[2]

Figure 2. Plan of the church as it appeared in 2006–2007.

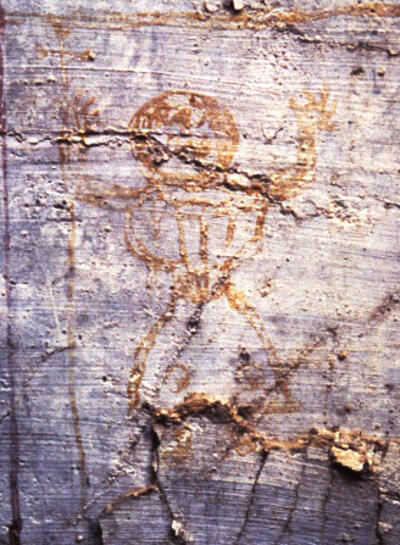

Another unusual feature of the church is the subterranean chamber located under the nave. It is built in white-plastered mud brick and accessed via a narrow shaft on its north side. There was originally a second room to the west, which was deliberately closed. These rooms predate the church and were initially thought by Peter Grossmann to belong to a dwelling similar to early fifth-century examples at Kellia.[3] In a more recent publication Grossmann suggests that this is an early church, comparable to those of the fifth century at Kellia.[4] Inside the chamber, the Scriptorium excavators discovered a simple wall painting of a monk identified by an accompanying inscription as “John” (fig. 3). It is not certain whether this painted figure represents John the Little because several monks named John were associated with Scetis. Evidence from medieval literary sources suggests that the bodily relics of John the Little were deposited within the church at the Monastery of St. John the Little when it was rededicated in the first decade of the ninth century. It likely that, even before this time, the location had been marked as a place of veneration.[5]

Figure 3. Wall painting of a monk named John in the subterranean chamber beneath the church.

[1] Samuil and Grossmann, “Researches,” 360.

[2] For a detailed description of the church, see: Samuil and Grossmann, “Researches,” 360–361; Grossmann, “On the Church,” 21–28.

[3] Samuil and Grossmann, “Researches,” 361; P. Corboud, “L’oratoire et les niches-oratoires: Les lieux de la priere,” in Le site monastique copte des Kellia: Sources historiques et explorations archéologiques, Actes du Colloque de Genève, 13 au 15 août 1984, ed. P. Bridel (Geneva: Mission suisse d’archéologie copte de l’Université de Genève, 1986), 88, fig. 2.

[4] Grossmann, “On the Church,” 27–28; G. Desœudres, “L’architecture des ermitages et des sanctuaries,” Les Kellia: Ermitages coptes en Basse Égypte, ed. N. Bosson and Y. Mottier (Geneva: Musèe d’art et d’histoire de Genève, 1989), 33–55.

[5] Stephen J. Davis, The Arabic Life of St. John the Little (Coptica 7; Los Angeles: St. Shenouda the Archimandrite Society, 2008), 14–15.