Architectural Conservation in the Church

The nave of the Church of St. Shenoute at the White Monastery has been without its roof, as well as much of the colonnade of columns that supported a first-floor gallery, for centuries, probably due to an earthquake during the medieval period. The lack of lateral support that the roof provided to the structural enclosure of the nave was a major factor that led, over time, to the deformation, of its north wall, which towers 13 meters high and runs unsupported over its 48-meter length (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Deformation of the north wall of the White Monastery Church as it appeared in April 2019, looking east. Photograph by Gillian Pyke.

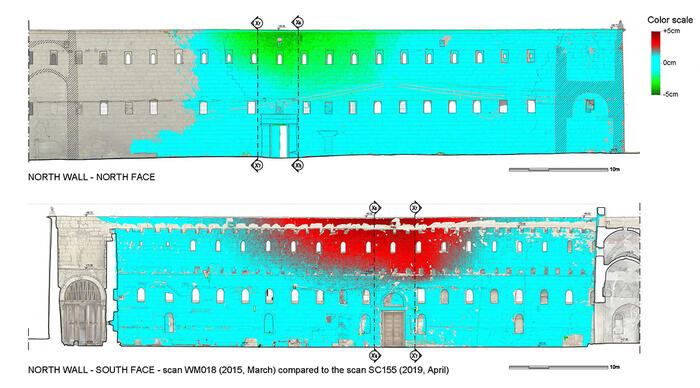

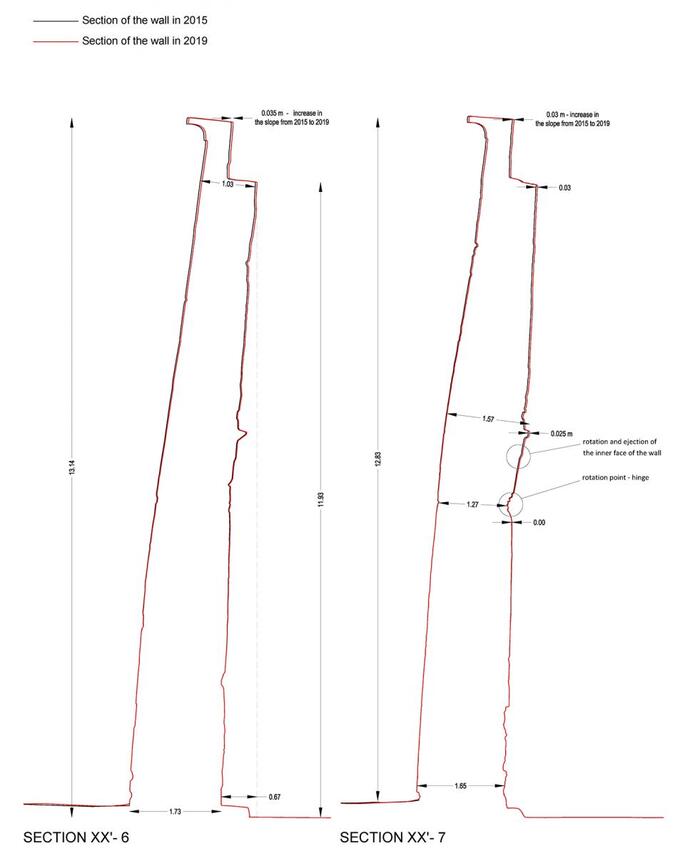

In 2015, the inward bowing of the upper part of the wall was mapped for YMAP by CPT Studio Roma through a 3D terrestrial laser scan. The scan was repeated in 2019 (fig. 2), allowing the progress of deformation to be tracked with millimetric precision (fig. 3). This showed that conservation intervention to stabilize and support the wall was urgently needed. At the most severe point of deformation, the wall had shifted over a period of four years by seven millimeters, resulting in a total inclination of 72 centimeters ‘out of plumb’ across its full height. On January 6, 2022, after heavy rainfall, a section of masonry at the center of the south face of the wall collapsed (fig. 4).

Figure 2. Change detection of the north wall deformation using the March–April 2019 3D laser scans. Image by CPT Studio Roma.

Figure 3. Sections through the north wall in 2015 (black) and 2019 (red) from the 3D laser scanning. Section XX’-6 shows the increase of the slope in the upper part of the wall to be 3.5 cm and Section XX’-7 shows the increase of the deformation in the central part of the wall and the rotation and ejection of the inner face of the wall. Image by CPT Studio Roma.

Thanks to a generous AEF grant it was possible to begin work on the detailed conservation plan developed by the project’s structural engineers. This plan combined stabilization using stainless-steel bars to pin the two faces of the wall together, deep pointing of the masonry to replace mortars that had lost their cohesion, and selective stone replacement, with rebuilding of the lost portion of the wall and permanent support on the wall’s south side.

Figure 4. The collapsed portion of the south face of the north wall, looking northeast, in April 2022. Photograph by Gillian Pyke.

The anchoring system forming the core of the conservation intervention was developed and installed by a UK-based structural engineering company Cintec International. The company is renowned for its innovations in engineering solutions for the structural anchoring and reinforcement of historic buildings, and has worked on several projects in Egypt. The Cintec anchoring system is a reinforcement method particularly suited to historic buildings because it causes minimal disruption to the structure. It consists of a custom-made stainless-steel bar (‘anchor’) enclosed in a flexible woven polyester sleeve into which a grout is introduced under low pressure (58 psi; figs. 5-6). The anchors typically have a 10 mm diameter, but thicker anchors (in this case 16 mm) may be used for additional strength. Each anchor is installed through a 40 mm drilled bore hole produced by dry diamond coring technology, which has no percussive action that might damage the surrounding masonry (fig. 7). The permeable sleeve inflates and molds to the shape of the space within the wall during the grouting process, which allows the grout to form a strong mechanical bond that locks the anchor in place.

Figure 5. Dennis Lee and Hanna Maher Matta preparing the anchors and sleeves for installation during conservation work in December 2023. Photograph by Hanna Aziz Adly.

Figure 6. Essam Ali al-Sayed Ali ensuring the pressure remains low while adding the grout to the installed anchor in March 2024. Photograph by Gillian Pyke.

The wall was further strengthened through deep pointing of the masonry and brickwork (fig. 8), which together with limited stone replacement was carried out by Intro Group, a local engineering firm. The pointing has several functions: re-establishing stonework (and, in some cases, brickwork) bond; increasing weather resistance; and eliminating bird-perching points. Stone replacement was minimal and undertaken only when load-bearing blocks had failed, threatening the stability of the wall.

A total of 421 anchors were installed during the season, representing approximately 70% of the below-gallery area of the interior face with an additional intervention on the exterior face to cross-stitch a substantial vertical crack. Approximately 35% of the below-gallery area of the interior face was repointed, almost of which was in its western part, with additional work associated with specific interventions on the exterior face. Stone replacement was necessary in the westernmost niche, the niches either side of the main doorway and the exterior lintel of the lower-level window to the east of the main doorway.

Figure 7. Joshua Hart, assisted by Ashraf Safwat Maher, drilling the borehole to receive an anchor within the framework of the support structure in December 2023. Photograph by Hanna Aziz Adly.

Figure 8. Dennis Lee, Mohamed Nadi Haddad and Ibrahim Abdel Hamid repointing brickwork above the central doorway on the exterior of the wall in March 2024. Photograph by Gillian Pyke.

YMAP’s mission to conserve the north wall of the White Monastery church is only in its early stages, and there is a long way to go before the process of rebuilding the fallen section of wall can begin. This slow progress is necessary because new engineering challenges reveal themselves as each new location requiring intervention is assessed. Time spent now in carefully developing and implementing the correct solution to each of these challenges will ensure that when the moment arrives for rebuilding, the work can proceed safely. Step by step, the structure of the White Monastery church is being secured for the future.